The Right Every Man Should Have

‘Until it burns out with the sun, my vocation is to love Earth, not escape it, to practice caring for it and the other people and places that are here.’

Robert Sheckley wrote “The Store of the Worlds” in 1958, a short story haunted by the possibility of nuclear (or thermonuclear) apocalypse. The story ends in “flat fields of rubble, brown and gray and black.” Its main character, Mr. Wayne, sports a “wrist geiger” that he uses to find a “deactivated lane through the rubble” that can take him “back to the shelter before dark,” when the rats come out. It is a bleak ending to a bleak story about the end of the world as we know it.

Sheckley was living in Manhattan at the time, under the shadow of pervasive American anxiety about atomic and hydrogen weapons. The United States had dropped atomic bombs on Japan in August 1945, instigating an arms race between the US and the Soviet Union, and throughout the 1950s, American life was preoccupied with the possibility of nuclear war. The Office of Civil Defense Mobilization produced a helpful pamphlet in 1958, “Facts about Fallout Protection,” explaining what fallout is and how you could protect yourself from it in case of a hydrogen bomb explosion. “Fallout will sift into your house or shelter like dust. Stop up the doors and windows tightly.” A black and white, line-drawn figure sealed the windows with lime green caulk. The pamphlet advised building a shelter supplied with two weeks of food, and it pictured a nuclear family enjoying their shelter. The children were busy at checkers. The pamphlet didn’t say how long the fallout would take to decay.

“Facts About Fallout Protection,” pamphlet produced by the US Office of Civil Defense Mobilization, 1958.

One apocalyptic moment can easily transfigure into another, though, as we have learned in the intervening years, and Paul Franklin’s short film adaptation of Sheckley’s story is a made-for-climate-emergency movie. “The Escape” (2017) does not end with reference to nuclear apocalypse; instead, it foresees the end of civilization by flood. The last shot pans up across tidal flats to show London’s skyline submerged in sand and water. You can still see the clockface of Big Ben, but barely.

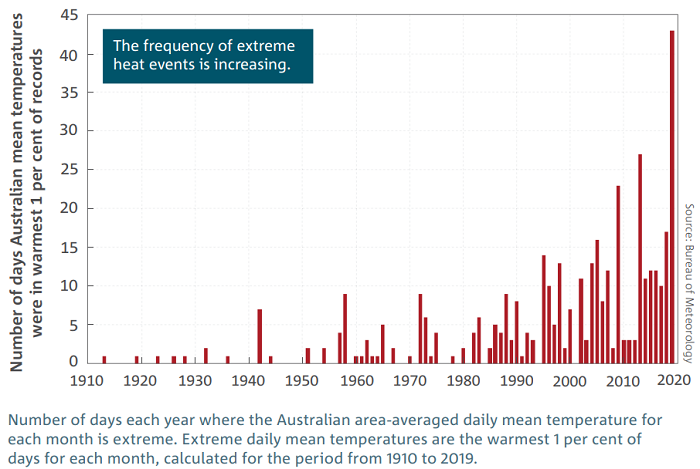

I am sympathetic with the turn to apocalypse, given the current state of things (though since last summer’s fires I’m more consumed with heat than flood for the moment.) The frequency of extreme heat events is increasing in Australia at a terrifying rate, and the chart that shows just how much more frequent and how fast is enough to put anyone into an apocalyptic mood.

From the future, this next very hot decade is going to look cool, and lots of places are going to get harder and harder to live. I am myself sometimes tempted to think it’s going to be the end of the world.

This is the instinct that Sheckley’s story appealed to – an entirely understandable fictional play with the terrors we are in fact facing, and a question about what it would be like to face them. Lots of people (prominent theologians among them) are inclined to think that this sort of experiment can help reveal important things about our world. They point out that apokalypsis means “revelation,” not “cataclysim.” If we look to a dark future in stories like Sheckley’s, perhaps apocalypse can reveal something about what our lives are now and what to do with them. Stories like this might teach us to value the lives we have better and inspire us to work for the politics required to sustain them.

But I am going to admit – frankly – and in the spirit of conversation, which is to say I could be persuaded to change my mind, that Sheckley’s story struck me as a perverse example of this kind of experiment, one premised on an anthropology I find deeply alienating and ultimately counterproductive to ecological commitment. Much of my research points toward the idea that you can’t do environmental ethics without social ethics. Flourishing ecologies must include justice within human communities, and just human communities include their ecological neighbours as morally salient members (I make something like this argument in my forthcoming book, Thoreau’s Religion. So here, I am going to focus for a moment on a matter from social ethics. Aside from the themes of environmental apocalypse in the story, the most prominent tropes are about gender and sexuality. I gotta say, I didn’t like them.

At the beginning of Sheckley’s story, Mr. Wayne comes in from the rubble to the “Store of the Worlds” and meets its proprietor, Tompkins, “a tall crafty-looking old fellow.” Tompkins is an outlaw scientist working on research to make it possible for people to escape the devastated landscape into any number of other possible worlds. Under Tompkins’s care, you leave behind your body and travel to the world of your “deepest desire,” living there for a time.

Mr. Wayne presents as hesitant about this process from the beginning. When Tompkins suggests Mr. Wayne could be harbouring a secret dream of murder and end up in the all-murder-all-the-time world, Mr. Wayne cries, “Oh, hardly, hardly!” When Tompkins suggests it might be power he wants, and maybe he will become a god, Mr. Wayne demurs again. But Mr. Wayne gets more enthusiastic when Tompkins suggestions turn to sex, gluttony, and fame. And when Tompkins suggests Mr. Wayne might prefer something more low-key – “A simple, placid, pastoral existence on a South Seas island among idealized natives” – Mr. Wayne says, “That sounds more like me.” But travelling to the world of your deepest desire is expensive, and Mr. Wayne tells Tompkins he has to think about it. He heads home.

When he gets home, he is confronted by household responsibilities: a wife who needs him to manage a maid, a son who wants his help with carpentry, a daughter who wants to talk to him about kindergarten. Eventually, all the demands are taken care of, his children are in bed, and his wife – Janet – senses something is on his mind. She says he seems worried about something and asks whether he has had a bad day. He stonewalls:

“He certainly was not going to tell Janet, or anyone else, that he had taken the day off and gone to see Tompkins in his crazy old Store of the Worlds. Nor was he going to speak about the right every man should have, once in his lifetime, to fulfill his most secret desires. Janet, with her good common sense, would never understand that.”

The mundane, middle-class story continues: work is hard, the son wants things Mr. Wayne can’t afford, Mr. Wayne refuses to tell Janet what he is thinking about again, household tasks require attention, things at the office get better and then worse, atom bombs are in the news and the son wants to know about them, and suddenly a year has gone by with “very little time to think of secret desires.”

And then there is a twist, and Mr. Wayne wakes up in Tompkins’s shop, and we discover they are living in a nuclear apocalypse. With this new knowledge, we can see that instead of gluttony, sex, and fame, Mr. Wayne’s deepest desire was for the life he lost and the family that is gone. The story has three sections: A) in which Mr. Wayne enters the shop and we don’t know he is living in nuclear apocalypse, B) in which Mr. Wayne lives his life with his family, and C) in which Mr Wayne returns to the real world and we discover he was seeking escape not from mundane middle-class life but from nuclear apocalypse. There is an obvious moral: mundane, middle-class life is better than it might seem to readers who are presently living there. Not getting exactly what you want is fine relative to nuclear apocalypse.

The story seems set against itself on the matter of male privilege. On the one hand, it may be trying to subvert exploitative masculinity – the protagonist refuses, after all, violence and idealized sex, even in the world of his deepest desire. On the other hand, perhaps unwillingly, the story reinscribes a sense of entitlement that I find revolting. The story – and the Store of the Worlds that is its central feature – springs from one major premise: “the right every man should have, once in his lifetime, to fulfill his most secret desires.” The gendered language is not an accident and it is not required. Whether what he wants seems nice or not relative to contemporary gender norms is beside the point.

It was written, though, again, in 1958, almost ten years before the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission declared age restrictions on flight attendants’ employment to be illegal sex discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Until 1968, you had to be a young woman to work as a flight attendant. In this context, Sheckley probably did intend to undermine common gender stereotypes.

And this contextualist reading does play out to a certain extent in Franklin’s film adaptation, which seems to suppress some of Scheckley’s more dated gender stereotypes, especially by rendering hyper-masculinity slightly revolting (that scene with the businessman eating steak, talking with his mouth full about his divorce) and by rendering plausible the desirability of ambivalent family love (that shot of their hands, clasped, as their daughter drives away). But in Franklin’s film, the premise about what a man deserves is stated in an even grosser way, in the voice of the outlaw scientist, who, trying to convince the protagonist to go for it, says, “Every man deserves a moment of pure release, wouldn’t you agree?” The 2017 film retains the gendered language by choice – an easy alternative would have been “Everyone deserves a moment of pure release.” It’s a choice that makes one thing vividly clear: the story is about men wanting to get what they want for once.

But the thing about wanting is that we never do it just once. Desires do not come to us from some elsewhere, otherwise, infinite number of other possibilities. Our lives our finite, and – as is becoming every day more apparent – our Earth is finite. We live in a world that is built to make us want things that are bad for us. We are taught what to want. But this is also cause for hope. We can practice wanting different things. We can teach our desire, through practice, to long for what is actually good for us, our families, and our communities. This is, I think, what asceticism sometimes is: the exercise we do to create wholesome desires. Rather than walk into the Store of the Worlds, we might embrace this world – Earth – and learn to long for a flourishing future here.

Until it burns out with the sun, my vocation is to love Earth, not escape it, to practice caring for it and the other people and places that are here. Climate apocalypse is certainly a temptation at the moment. Sometimes I think it would be nice if all the humans just disappeared. Maybe more species would survive that way. But I have been convinced by reading Indigenous thinkers like Tyson Yunkaporta that climate apocalypse like that is a cowardly renunciation of the human vocation as what he calls a “custodial species.” Our responsibilities do not end when we face devastation. Even after a nuclear apocalypse, there is still Earth, it is still our home. Humans have long shaped their ecologies for good, they are doing it now in countless places, and we should keep doing it as long as there is life on Earth to love.

Alda Balthrop-Lewis is a Research Fellow in the Institute for Religion and Critical Inquiry, ACU. She has completed a B.A. at Stanford University, a M.Div. at The University of Chicago and a Ph.D. at Princeton University in Religion, Ethics, and Politics. She has taught in the Religious Studies department at Brown University, and she has worked as a research assistant for the Peabody Award-winning public radio program On Being, produced in the United States. Her research focuses on religious ethics and the circulation of ideas among theological, artistic, and popular idioms. Her first book has recently been released, Thoreau’s Religion: Walden Woods, Social Justice, and the Politics of Asceticism (Cambridge University Press, 2020)

Images used are sourced from unsplash.com