Hoping for Common Ground with Technocrats

Factory workers are treated like machines. They are counted, rather than named. They are trained with documents that read like software programs, under the assumption that sufficient training will create high quality, repeatable products. This is worse than commodification, it is technification…

To look at my career is to see a typical story of an engineer and manager in manufacturing. Over that time I’ve learned the language of business, corporations, and capital. I can run the numbers, make dazzling graphs and charts, and talk at length about corporate strategy. This is a perspective from inside the engine of capitalism.

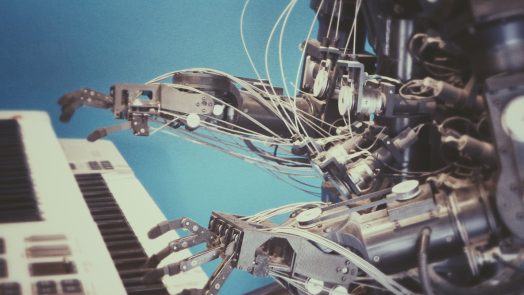

The technocratic worldview that this kind of career engenders is powerful. When I think about the people I’ve worked with over that time, I’m left with a consistent theme: “Machines are superior to people.”

Machines can be programmed, modified, bought, and sold. They can work continuously, faster, and consistently. They produce the same repeatable output for as long as they are switched on and fed with raw materials. This attitude has an unintended consequence: factory workers are treated like machines. They are counted, rather than named. They are trained with documents that read like software programs, under the assumption that sufficient training will create high quality, repeatable products. This is worse than commodification, it is technification; a violent transformation of the human into a machine.

Perversely, the same technocratic people who hold those views will sometimes flock to a product that is hand crafted. Artisanal beer, food, clothes, bikes, and more are prized possessions. Prized because such items are the result of a crafter who creates, who is not programmed, who is skilled more than a “mere” factory worker.

Such a focus on technology has other unintended consequences. Perhaps second only to professional athletes, technocrats are superstitious. In the face of the unknown or the unpredictable or the organic, they will invoke luck. “Fingers crossed!” they say, but only if they don’t tap the nearest piece of wood a couple of times (the nearest piece of wood is usually MDF, an artificial panel of glued sawdust created from the complete disintegration of trees, then covered with resin, sometimes patterned to look like timber). I speculate that heavy technocentrism has left no room for the uncertain or the vague, and manifests in the form of small superstitions. This mentality has developed no way to process unquantified knowledge.

It would be a revolution to break people out of this; a complete destruction of a way of seeing and thinking and acting in the world. It might also be a mistake. Quantitative analysis has its place but when it becomes ubiquitous it speaks death into the world.

From outside the managerial structures of a corporation there’s probably very little disagreement that companies need more humanity in their decisions. Even as I write this from inside such managerial structures, that’s clear. Despite the sense that it’s needed, there is little momentum towards it. The great quantitative measure – profit – overrules qualitative inputs at almost every stage.

Almost. Without a doubt, qualitative decisions happen in managerial structures. We need only look at Murdoch media to see how unsubstantiated opinions have made their way from the boardroom to the headlines. The results of climate change research (a process that follows all the rules of quantitative analysis) is ignored under a qualitative opinion that earns the company more money. Similar examples can be seen across various government policies.

Current standards of business management education are sorely lacking in this area. Many MBA degrees either omit this or deliver a reductionist version of it. Even worse, some give the tools for how to create modelling that quantitatively justifies your preferred qualitative inclinations. Few and far between are degrees that take it seriously. Our education systems continue to produce copies of what already exists while our corporate management structures make no demands for this to change.

And yet, employees make such demands. We leave organisations because they lack intelligent emotional support and decision-making within structures and from managers. The hours at work are hours of a person’s life, with personal needs that extend beyond the value that the person’s labour brings.

None of this is impossible. People can be taught to make decisions with both quantitative and qualitative input. No one is born with those skills, it’s learned. At its worst, it may result in a kind of “capitalism with a human face.” At its best is a hope for a way to make decisions within organisations, bringing together these disparate ways of working together and seeing the world.

Written by Andrew Smith, a manufacturing management professional, currently working in the medical device industry.

Images used are sourced from Upsplash.com