No-Bodies: on the imageless image of God.

‘The difficulty, then, is not simply to step outside of Feuerbachian projection. There is no simple or directly available outside. The difficulty is to open up within our projections, within the mutually implicated meanings of God/s and self, a movement that resists the inevitable slide toward stability and identity and therefore normativity’

‘God created man in his image, and man, being a gentleman, returned the compliment.’ Mark Twain

‘God Is Not a Man, God Is Not a White Man.’ Carol P. Christ

Michelangelo

The Creation of Adam

1512

Paint, Plaster

2.8 m x 5.7 m

(wikimedia commons)

Despite the so-called secular turn, religion continues to be a powerful and symbolic institution in the construction of sociality within communities. As do religious images of God. Consequently, the psychological, political, and social affects of embodied gods require interrogation against changing constructions of religious authority, even more so as the Western-centric/patriarchal foothold on religion is rightfully critiqued. A common response to the problematic closure that a normative image enacts – such as an image of a god – has been to multiply the subject and its embodiment, to create a diversity of subjects or representations of an embodied divine as a way of disrupting the hegemony of a single normative representation.

The move to multiply images of an embodied divine as a way of resisting oppressive normativity can perhaps be seen most clearly in the multiple non-normative representations of Christ that have emerged in recent decades. These are depictions that represent Christ beyond the normativity of a white, adult, able-bodied male. In 1975, British artist and sculptor Edwina Sandys infamously produced a bronze sculpture of a female Christ titled “Christa.”

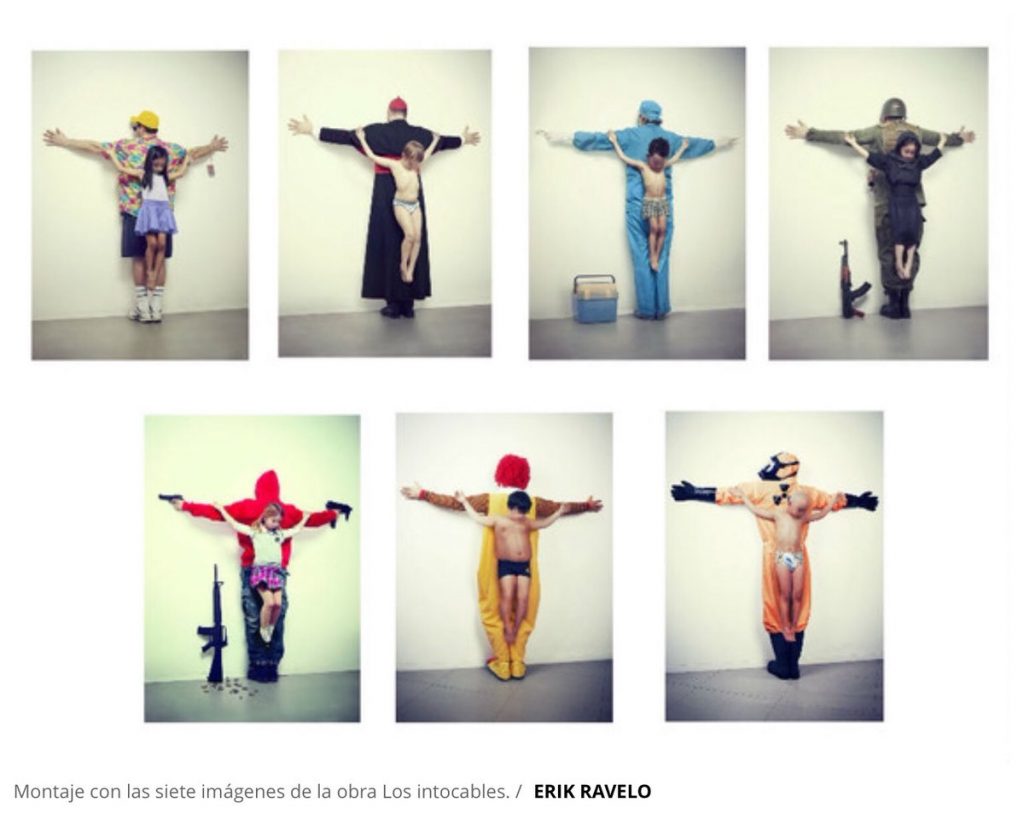

In 1999, the American artist Janet McKenzie won a National Catholic Reporter award for her painting Jesus of the People. The painting was intended to be “inclusive of groups previously uncelebrated in [Christ’s] image, especially African Americans and women”. More recently, the American television network Adult Swim has produced a comedy series titled Black Jesus that depicts Jesus living in modern-day Compton, California. Non-normative depictions of Christ have also focused on aspects such as weight, attractiveness, and age. The Colombian figurative artist and sculptor Fernando Botero has produced multiple paintings of a voluminous – often received as a fat -Jesus that move against the overwhelming tendency to depict Jesus with a lean, normatively attractive figure. Cuban photographer Erik Ravelo recently released a series of photographs titled Los Intocables (The Untouchables) that depict children hanging from a cross like Jesus, only instead of hanging from a wooden cross, the children are hanging from the cross-shaped bodies of soldiers, surgeons, priests, and Ronald McDonald.

The effect of such non-normative images of Christ is undoubtedly powerful. They have the capacity to disrupt the meaning-making mechanisms that produce an assumed, unquestioned normativity. Expanding and multiplying the representational range and capacity of a central religious symbol shows that a symbol is never the site of just one meaning. Symbols are always contestable, able to be redeployed and re-presented in limitless iterations that (in principle) can appeal to a limitless multiplicity of subjects. Moreover, multiplied symbolic subjects reveal the contextual and particular nature of all symbolic meaning making. When placed next to a black, fat, or female Jesus, the white, lean, male Jesus shows itself for what it is, a contextually produced representation that is the product of local and time-specific demands for meaning, for inclusion and exclusion. The Anglo-Saxon Jesus can no longer claim universality for itself. Or if it does, this gesture can be seen for what it is, a grab at power and control.

The potential gain of such multiplicity is that it creates space for marginalized imaginations about the possibilities of embodied divinity and bodies in relation to the divine. And with a broadened imagination comes a widened space of recognition for non-normative subjects and identities. Yet insofar as the strategy of multiplication still relies on the attractive power of identity, on the pleasure of recognition and the primacy of the subject, it perhaps cannot completely give way to subjectivity, to the self-in-becoming whose truth is found not in the forms and identities it inevitably assumes but in the movement between and beyond them. This is a movement responsive not to the pleasure of an identity gained but to the more difficult pleasure of ceaselessly becoming again what one never was.

It is perhaps an inevitable limitation of the way images and forms, even images and forms of non-normative subjects, work: forms signify within image repertoires that inescapably normalize. The move to image and therefore identify inevitably creates the conditions of exclusion, even when what is being imaged is what was once excluded. There is always somebody, or some nobody, who falls outside of the normed frame. Identity needs excluded others. Even in practices that radically multiply images of embodied divinity, the Feuerbachian game of projection is still in play. And so perhaps, a very different way to think about bodies—God/s bodies, and human bodies—is required.

The Apophatic Body

To imagine that humans could be entirely free of the desire to project and secure idealized representations of themselves is perhaps simply the flip side of that very desire, a desire that at heart harbors a longing for purity and finality, even if it is the purity and finality of an absolute rejection of any and all images. This is perhaps the temptation of certain Protestant theologies insofar as they are determined by a rejection of Catholic and Orthodox iconography and sacramental presence.

As I have suggested, God/s are inescapably a screen or mirror on which the self projects itself and in which the self is reflected back to itself. This need not, however, be regarded always and only as a pernicious, self-deluding, or idolatrous gesture. Jewish and Christian theology—and parallels can be found in Islamic and Hindu theology—have long acknowledged that God “accommodates” to human language and imagination, to representations that are determined by human limitation and embodiment, even as God is never objectively captured by any of them. Such accommodation reaches a scandalous climax in Christianity’s paradoxical claim that God becomes an actually existing human being while remaining God. Moreover, the Christian spiritual tradition is in one sense a long reflection on and wrestling with the inseparability of God and self. There is no self without God and no God without self. In The Sickness unto Death, Kierkegaard sums up an entire spiritual tradition: ‘The greater conception of God, the more self there is; the more self, the greater conception of God’ (1990, 80). “Self,” however, denotes not a stable or identifiable object with a settled form but a site of relation in which form comes into existence only within a movement that infinitely exceeds and therefore undoes it, demanding ever new forms that in turn are only ever to come undone. A self alive before God is not a settled subject but an unsettled movement of subjectivity in which, as Kierkegaard puts it, ‘there is no standing still’ (1990, 94).

The difficulty, then, is not simply to step outside of Feuerbachian projection. There is no simple or directly available outside. The difficulty is to open up within our projections, within the mutually implicated meanings of God/s and self, a movement that resists the inevitable slide toward stability and identity and therefore normativity. I am suggesting that the strategy of multiplying embodied subjects and identities is only ever on the way to meeting this difficulty. Multiplying images and identities does not as such open up movement. It simply increases the options for how to stand still.

The problem, however, is not with embodiment, as if embodiment as such entails static identity and therefore normativity. The problem is with the presumption that the body is a site of rigid identity rather than a site of unmasterable movement and relationality. To think and represent the body as movement—that is the challenge. As Graham Ward puts it:

‘A body is always in transit, always exceeding its significance or transgressing the limits of what appears. The body is constantly in movement and in a movement… The body exists fluidly in a number of fluid operations between reception and response, between degrees of desire/repulsion, recognition/misrecognition, and passivity/activity. These operations maintain the body’s mystery by causing it always to be in transit. As such a body can only be reduced to a set of identifiable properties of its appearance (such as identifications of sex as “male” or “female”) by being isolated from these processes and operations; by being atomized.’(2007, 84)

In other words, the body never stays put. Identifying labels, such as those of concrete, stable gender, often function by isolating the body from its movement. The body, however, is always more than the labels it acquires. The body, always in transit that as such exceeds identity and normativity, might be called the apophatic body.

Apophasis is called for, then, not simply when it is a matter of speaking of God but also when speaking of all that is related to God, including the body. In relation to God, the body also becomes uncapturable in language and form. The apophatic body, the body un-said or said-away from capture, is a kind of no-body, the body slipping out of form, the body becoming itself as movement. To represent the body as no-body, as unmasterable movement, is perhaps—there can be no guarantee here—to hold open a space for subjectivity, for the calling of the self into existence beyond identity, into the difficult pleasure and joy of ceaseless movement. It might help here to think of your own body and all the changes that have taken place within it during your lifetime. How could a single image every capture that or tell a clear story of who you ultimately are?

No-Bodies: on the imageless image of God.

Perhaps something of which I am pointing to can be seen in ‘The Last Supper’, a painting by American Abstract Expressionist, Mark Tobey. Though driven by a deep sense of unity, Tobey’s work represents both differentiation and de-formation of bodies; both God’s body and those bodies in relation to God and therefore each other. This unity is expressed ‘in a fluid circular structure within which the figure of Christ becomes a central core…The table, defined in part by the figures around it, is also circular. Black and white lines appear to flow, to include angels and curves, to be differentiated yet somehow unbroken. More agitated curves and spirals move outward to the white negative space at the top of the painting, and the cross slanting toward the left-handed corner remains anchored; death is not cut out from life’, not cut off from bodies together and bodies unknown. Tobey’s sense of the apophatic, learned through his own religious pilgrimage, allows for what is described here as a kind of ‘meditative playfulness’, or ‘the playing with shape and line, the effect of a building up backward, the movement between negatives and positives, the gradual emergence of figures and subjects’ that are never given over to some kind of stable representation or enduring form. What surfaces is a deluge of movement and fluidity, and what we are left with is more of an imageless image of God, and imageless image of ourselves. Beyond and without the normalising images that typically represent to us a God and a self, The Last Supper signifies a de-formation of such bodies, and in doing so, opens the possibility of subjectivity, of relation.

These bodies are elusive, depicting limbs arranged in ways that suggest nothing apart from relation. Is the viewer to see one body assuming multiple forms? Multiple bodies each with its own form? Are the bodies embracing each other? Themselves? Nothing? The use of lines across the paintings disrupts their form and suspends them in uncertain moments of coming into existence—or perhaps in uncertain moments of going out of existence. Significantly, the bodies, or no-bodies, bear no obvious identity markers, and if the movement is read eucharistically, which I’d suggest it should be, then it is movement which names the opening of the self to the divine other, an opening so radical and an other so other that the self loses any stable grasp on itself. Indeed, in the eucahristic movement relation is only possible because we’ve simply given up trying to become masters of bodies and identities: God’s bodies, and ours.

The bodies of The Last Supper are held open by the nothing apart from the relationality of the movement, the movement of their relationality, which is always played out on the backdrop of no-thing in particular, of no content and form. The white negative space at the top of the work indicates this subtly: beneath and beyond all discernible form, all finite difference abides the eternal difference of infinite relation, the relation of the eternal to itself, here represented as the relation of negative space to the movement of subjectivity it at once signifies and embodies. It is this infinite difference that both makes possible all finite difference and holds relation open to what exceeds and undoes relations normative arrangement: the divine call into selfhood that holds out not the pleasure and promise of an identity gained but only the joy of relation itself, forever unmasterable. God here moves back to an embodied formlessness, an imageless image—not the simple absence of form but it’s setting in motion well beyond any normalising frame.

Written by Janice McRandal, Director of the cooperative.

Portions of this essay originally appeared in an extended essay as: ‘Embodied Gods’, McRandal, J., 2017, Gender: God. Hawthorne, S. (ed.). 1st ed. Farmington Hills, Mich, USA: Macmillan Publishers, p. 63-78 15 p.