An architecture of complexity and contested value

‘On mentioning my research, the church building I am frequently asked about is Holy Family. Architects, engineers, clergy, parishioners, academics ask about its design influences…’

An architecture of complexity and contested value

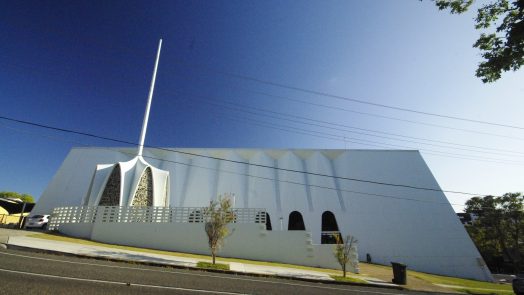

Holy Family War Memorial Catholic church at Indooroopilly (1960-1963), designed by the Brisbane-based practice of Douglas and Barnes, is comprised of highly sculptural and geometric architectural forms, and constructed using various complex reinforced-concrete construction methods, which still today would present construction challenges. In recognition of its bold and innovative design, this year, Holy Family was awarded the Queensland chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects enduring architecture award. However, as much as it is a Queensland exemplar of modern architecture, its forms and construction appear to be an aberration.

At the beginning of 2016 I embarked on a doctoral project (now under examination), studying Queensland’s post-war (1945-1977) modern church buildings. For five years I have collated the architectural history for over 5500 church buildings throughout Queensland, of which over 1350 were built during the post-war decades. Amongst these many churches were many very basic buildings, but also numerous highly accomplished architectural examples, 90 of which I write about in my dissertation. For my research I have visited over 300 modern ecclesiastical buildings, most within Queensland, and some interstate and abroad. During my doctoral candidature I have written two peer reviewed papers, a journal article (which lead to the invitation to write this piece) and a book entry on the architecture of Holy Family. So, as you read this, it will not surprise you to know that I have an engaged interest in the architecture and artwork of the Holy Family and admire the boldness and ingenuity of its architect.

The intrinsic interest I have for modern church architecture lies with the complex changes post-war architecture underwent – not least the huge shift from Gothic and Romanesque architecture to modern, which Holy Family ‘partly’ completes (as I will explain below) – and the concurrent shifts in society, religion, all concurrent with the development of modern Queensland. The post-war decades were a time of massive and continual change, which lead to some highly experimental pieces of church architecture. I would argue (as I have in my doctoral dissertation) that from 1959 till 1963 church architecture propelled the discipline of architecture, as church buildings were used to experiment with modern material, technology and construction methods. Holy Family is the standout example of these innovative years.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s a genuine church building boom occurred in Queensland (as elsewhere in Australia), which also continued into the mid-1970s. The height of this boom was 1958, when at least eighty church building were opened in the state. Various religious historians have identified 1959 as a peak in the city’s religious celebrations. This was the year when the crusade of Bill Graham (an American evangelist) held outdoors religious events, which in Brisbane gathered thousands to hear him speak. In many townships throughout the state, and most of Brisbane’s suburbs new church building were built for multiple denominations during this era. In Indooroopilly, eight new church/chapel buildings were erected during the post-war decades – two Anglican (St Peter’s Moggill Road now used converted a childcare facility), two Catholic (with the chapel for Xavier’s teachers demolished in 2017), a Presbyterian (demolished in the late-1970s), a Methodist (now Uniting), a Baptist and a new chapel at St Peter’s Lutheran College. Thus, Holy Family was designed in a time of religious and architectural optimism.

It is now over 50 years since Holy Family was blessed and opened. Like many bespoke modernist buildings, Holy Family raises many questions, particularly for the local Catholic Church and its religious congregation, but also for its suburban neighbours, historians, heritage groups and the architectural profession (and arguably more so than any other Queensland church building). These questions reveal an ‘uneasy heritage’ and numerous ‘contested values’. Today a multitude of divergent views are held for: the sacred and religious; the devotional, ritual and symbolic; architectural, engineering and artistic innovation; what is historical, cultural and heritage; landmark infrastructures and urban planning; ethical, monetary (maintenance and insurance costs and real estate valuations) and secular priorities; social, welfare and community value. Not surprisingly, Ann, John and Sera have touched on some of these in their written pieces.

On mentioning my research, the church building I am frequently asked about is Holy Family. Architects, engineers, clergy, parishioners, academics (and others outside these circles) ask about its design influences. How and why did the design of Holy Family occur in Brisbane? Admittedly at first there seemed to be no church building in Queensland frontrunning or following Holy Family’s example, and its ties to interstate also seemed few. So, during the last few years I have invested considerable time to answer this question. This enquiry revealed tensions in the transfer of modern architectural ideas from abroad to Brisbane and the appropriateness of doing so for the local climate, economics and the social priorities of the then still developing young city.

The architect William (Bill) Douglas (1930-2005) designed Holy Family in his early thirties, assisted by Harvey Blue (1938-). Douglas lived locally at Long Pocket and this was his parish church. Douglas and Blue studied architecture at the University of Queensland (then a combination of CTC and UQ), under the tutelage of lecturers lead by Professor Robert Cummings and the Austrian émigré Dr Karl Langer, and when modern architecture was only starting to infiltrate the department of architecture’s course work. From abroad, the 1950s and 1960s saw UK and US illustrated architectural periodicals transfer emergent ideas for modern architecture from the US and also Europe to Queensland. The parish priest was Father Victor Francis Roberts (1904-1975, Indooroopilly PP 1938-1973), who Archbishop James Duhig (1871-1965; Archbishop 1917-1965) delegated the design oversight, purportedly also admired modern architecture and travelled Europe ahead of commissioning Holy Family’s design. In 1961 slides from Roberts travels were used with a slide taken of Holy Family’s architectural model to convince the parish congregation of the merits of the design, enough to see them fundraise for its reported £70,000 construction costs.

However, Duhig did not praise for Holy Family’s design. In 1961, in his opening speech for St Joachim’s, Duhig described Holy Family’s design as ‘pretentious’[1] and from then on refrained from commenting in public. At the opening ceremony of Holy Family, Duhig stated:

I am not now going to enter into any commentary on this building, although what I might call its new features would tempt one to do so … there will no doubt be comment and criticism, for there are certain new features in the building that call for them, but that will pass.[2]

Locally other ‘modernising’ church designs were realised during the early 1960s. Holy Family was designed the same year as Duhig opened St Joachim’s Catholic church in Holland Park (August 27, 1961) and Our Lady Help of Christians in Hendra (December 3, 1961). These were the first two Catholic church buildings in Queensland to depart from the elongated rectilinear basilica church typology and adopted fanned plan arrangements. A few years prior, May 3, 1959, Duhig had opened the small and low budget (£9,000) church of St Monica’s Catholic in Tugun, stating ‘it is about time we returned to dignified Gothic and Romanesque architecture: modern ecclesiastical architecture is abominable’, and added ‘This looks like an army shed!’ A few days later, Brisbane’s Anglican Archbishop Reginald Charles Halse (1881-1962, Archbishop 1943-1962) at the dedication of St Francis’ Anglican church in Nundah said: ‘When I hear people say that modern building cannot rise up to the older standards I am prepared to say ‘come and see this new church’.[3] St Francis’ has a pleated ceiling, similar in aesthetic to Holy Family’s, as does St Andrew’s Anglican church (1955-1965) in Indooroopilly, only a short walk away. These church buildings are the some of the local frontrunners to Holy Family, though arguably nowhere near as extreme. They also reveal some of the tensions arising as designs shifted from Gothic and Romanesque towards modern, particularly as lower budgets were adopted.

Abroad, the widely published concrete churches of Auguste Perret, Dominikus Böhm, Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer, Felix Candela, and then Marcel Breuer and Peri Luigi Nervi had pushed the plasticity of concrete church architecture. Most notable of these is Breuer’s St John’s Abbey Church (1953-1961, Collegeville, Minnesota, US), which like Holy Family has an origami-like pleated concrete form. Interstate, Nervi’s unbuilt 1957-61 scheme for the New Norcia Catholic Pilgrim Cathedral (WA) proposed multiple parabolic arches, arranging them as the three intersecting arches pitched tall over a triangular-planned worship space. The eight tilted hyperbolic paraboloid arches of Holy Family’s baptistery chapel have a likeness to Nervi’s scheme. Interstate two ecclesiastical buildings opened just ahead of Holy Family. St Kevin’s Catholic (1961, Dee Why, NSW), designed by Gibbons and Gibbons, used both precast and post-tensioned concrete shell construction and parabolic arches to create a highly expressive pleated and draped structure. St Mary of the Sea Catholic Cathedral (1962, Darwin, NT), designed in 1957 by A. Ian Ferrier of J.P. Donoghue, Cusick and Edwards used reinforced-concrete parabolic ribs expressed as the entry façade and within the interior. Each of these overseas and interstate building provide context for Holy Family. Considering Holy Family within this global context, Douglas’ design (produced with the support and in collaboration with Fr Robert’s) was progressive but aligned with what was occurring elsewhere.

There were two Queensland ecclesiastical buildings, which if budget had enabled, might have been recognisable followers. St Monica’s War Memorial Catholic Cathedral (opened 1968), designed by Ferrier was initially tendered with a draped and pleated ceiling, and circular baptistery chapel. Budget limitations pared the built design back. St Andrew The Apostle Lutheran in Brisbane’s CBD (opened 1976), designed by Barry Walduck, was initially designed as béton brut (in-situ concrete structure and with a timber board finish), but following the winning tender’s advice it was instead built as double-sided brickwork filled with concrete.

So why were there not more church buildings in Queensland like Holy Family? Where are the church buildings to follow its lead? Cost, time (Holy Family took more than two years to build), the preferred local materials and construction methods, and emergent religious change (liturgical renewal) were all contributing factors.

Holy Family only ‘partly’ completes the shift from Gothic to modern, as its design did not respond to emergent ideas for liturgical renewal, which were formalised as part of the Catholic Church’s Second Ecumenical Council (Vatican II, held in Rome, 1962-1965). Its architecture’s materiality and form may fit the definition of modern architecture, but not the Church’s post-Vatican II need for ‘liturgically modern’ architecture. In planning, volume and atmosphere both Holy Family’s church and baptistery chapel are a transcendental architecture (terminology typically associated with Gothic churches). Holy Family is an elongated basilica in modern architectural dress and within only a few years after its opening Holy Family’s planning arrangement was outdated. Attempting to address post-Vatican II liturgical changes, a different arrangement was trialled from around 1978 till just after 2000, when the sanctuary was positioned along the southern side wall and the pews arranged in a wide arc around it. However, the building’s narrow width made this challenging, so the sanctuary and pews have been repositioned in the current arrangement, which varies only marginally from the original arrangement.

The architecture of Holy Family Catholic church embodies distinctive ideas from the years it was designed and built. In elucidating how such a design came to be in Brisbane, it is also evident that Holy Family presented and still presents challenging dualities. Holy Family was both innovative and traditional. It still now forces its congregation to use it as it was built, adaption for greater spatial flexibility is a costly proposition. It is a religious landmark that attracts those that admire modernist concrete while it repels those that do not. It is white, colonial, Christian heritage, but valued indigenous sacred sites continue to be destroyed across Australia. Holy Family has an ‘uneasy heritage’. Without doubt its values will continue to be debated. Indeed it will need its advocates to survive another 50 years.

Written by Lisa Marie Daunt. Following 15 years working as a practicing architect, 2016 saw Lisa return to the University of Queensland as a PhD Candidate. Lisa is researching Queensland’s post-war Church Building Designs critically analysing context, influences, trends and exemplars – asking how Queensland’s post-war church buildings contributed to building modern community in Queensland.

[1] Catholic Leader, August 31, 1961.

[2] Catholic Leader, November 14, 1963.

[3] Cross-Section, no.80 June 1959; “Memories of the beginning of the Tugun Parish….” written in 2009 sourced from the Catholic Brisbane Archdiocese Archive.